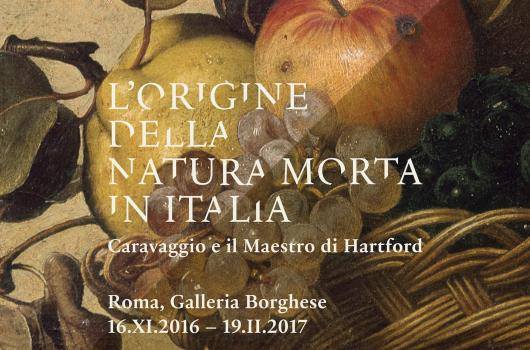

L'origine della natura morta in Italia.

Caravaggio e il di Maestro Hartford

The Galleria Borghese presents The Origins of Still Life in Italy: Caravaggio and the Master of Hartford, an exhibition that continues the process of valorizing its artistic heritage by analyzing the origins of Italian still life in the context of Rome at the end of the 16th century and following the subsequent developments of painting in the style of Caravaggio in the first three decades of the 17th century.The exhibition is curated by Anna Coliva and Davide Dotti.

For several years the Galleria Borghese has been carrying out a programme of exhibitions with various subjects and appoaches, all of which are focused on itself –on its perfectly and intensely historical nature as both a building and a collection. In every exhibition, the Galleria is not the location, but the protagonist of the event, indispensable in developing its theme. The one that we are inaugurating today is a strictly historiographical and philological opportunity to intervene in the itineraries of the Galleria to recount the origins of the genre of painting that only much later would be called natura morta (“dead life”) in Italian. In effect, 17th-century art criticism called such paintings oggetti di ferma, with the exact modern meaning of “immobile models”, as in the English-language expression “still life”.

Caravaggio was the first to confer on a fragment of nature depicted from life with dazzling realism the same formal and interpretive dignity previously reserved for portraits or sacred and mythological history. As the presence in the exhibition of the Basket from the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana attests, he was the first to establish still life as a significant subject on its own, full of symbolic meaning that had nothing in common with the “futile microscopes of the Flemish” (Roberto Longhi). The Basket is the work that first and in the most convincing forms imposes the pictorial representation of things simultaneously on one’s eyes and one’s consciousness and that, realizing in painting the reality of the object, proclaims the reality of the subject who paints it and the truth of the act of painting. Thus we can declare that the Basket inaugurates the great episode of modern art.

Before this time and this work, fragments of still life – which have been numerous throughout the history of art from the very beginning – were only parentheses within larger compositions, subordinated hierarchically to other subjects of representation, entirely incidental facts whose purpose was to demonstrate the artist’s technical skill in creating a perfect imitation of reality. The paintings that led to the extraordinary, perfectly executed conceptual leap realized by the Ambrosiana’s Basket and that gave rise to what we call a new pictorial genre were all present in the Borghese collection from its formation at the beginning of the 17th century thanks to the collector’s cravings of Cardinal Scipione Borghese: two paintings by Caravaggio – the Self-portrait as Bacchus (Sick Bacchus) and the Boy with a Basket of Fruit – and four still lifes that critics later referred to under the conventional name of the “Master of Hartford”. Especially for this reason, an exhibition such as this had to take place in the Galleria Borghese, because the vicissitudes of its birth and its success are intertwined with the history and the protagonists of this place.

The six works have been brought together again for the first time after four hundred years for this exhibition. All six of them were among the 105 paintings confiscated on 4 May 1607 from the Cavalier d’Arpino – the most famous artist and the most in demand of his time, as well as an important art impresario, a dealer, and perhaps a collector – by the papal tax collector as ordered by Pope Paul V, uncle of Cardinal Scipione, the creator of the Villa and the collection. The Pope immediately gave the paintings to his nephew to enhance the already famous gallery the latter was forming. That all six paintings were among those confiscated from the Cavalier d’Arpino was a documentary discovery by Federico Zeri, who followed it with the suggestion that – because of both the light as a factor of compositional synthesis and the “distinct representation of the most minute detail”, as well as because of the power and vividness of the objects depicted – the four still lifes by the Master of Hartford were the first, immature works of young Caravaggio, who was still in the studio of the older Cavalier d’Arpino. This critical hypothesis, which at the time (1976) was received with much fuss and some unseemliness, is no longer tenable, and this exhibition – whose catalogue will present the results of recent diagnostic investigations – will serve to confirm definitively that Caravaggio was extraneous to the execution of the works gathered under the name of the Master of Hartford. But that has in no way negated the validity of the basic claim that still life as an autonomous genre was born in Rome – in those paintings and in the Borghese collection – as part of Caravaggio’s naturalism. And the time frame of the exhibition consequently extends from 1593, the year of the Sick Bacchus, to around 1630, the year of the Flask from the Pinacoteca in Forlì, a powerfully inventive work of such high quality that it is still not certain which artist, among those active at the time in this genre, painted it.

In addition to its historical connection with the Galleria Borghese and the conceptual origins of the new genre of still life, the exhibition highlights very complex documentary questions through the contributions of specialists regarding provenances, autographs, and the membership in style groups of artists whose personal data are unknown because of the silence of our documentary sources, but are so well known from the stylistic point of view that they are grouped togther by scholars under fascinating names, especially the Master of Hartford, who is the main subject, because his still-life production is closely connected with several of Caravaggio’s works, including the Self-portrait as Bacchus (Sick Bacchus), the Boy with a Basket of Fruit, the Lute Player, and the Mattei Supper at Emmaus. Furthermore, for a long time Federico Zeri thought that the Master of Hartford could be ientified as the young Caravaggio.

As evidence of how the lesson of the Master of Hartford and the youthful Caravaggio was received by painters active in Rome in the first two decades of the 17th century, the exhibition displays the works of the “Master of the Little Vase”, the “Master of the Pink Apples”, “Saraceni’s Boarder”, and other prominent specialists.

Along with them are the painters who frequented the Academy founded by Marquis Giovanni Battista Crescenzi in his Palazzo alla Rotonda adjacent to the Pantheon: Pietro Paolo Bonzi, known as Gobbo dei Carracci; the “Master of the Acquavella Still Life”, whom some scholars identify as Bartolomeo Cavarozzi; and Crescenzi himself, to whom scholars attribute several works, including the Fruit and Vegetables on Wood and Stone Shelves from the Galleria Estense in Modena.

We are indebted to Roberto Longhi for the most appropriate words for distinguishing the before – before the great, fervid elaboration of the new subject of still life that was in store for these painters – from the after. The before: “the futile microsopes of the Flemish, the extreme degeneration of the lenticular acuteness of the great but dangerous Nordic 15th century, which was now declining into work based on endless, nun-like patience.” And the after: “By now Mario dei Fiori will be painting festoons of vegetables on the dressing tables of Roman princes. Simple ‘still life’ is dead and buried, together with the spirit of Caravaggio. And as for the composite ragbags somewhere between the ‘baroque’ and the old Nordic diligence, it is better to hold one’s peace.”